S. Naval Institute

Proceedings, Vol 148/2/1,428

by Rear Admiral Cynthia Kuehner

February 2022

As part of the One Navy Medicine team, Navy nurses represent an essential component of advanced and complex medical weapons systems. Just as tactical weapons, cyber threats, warfare strategy, and the pacing capabilities of U.S. enemies have evolved, matured, and become ever more complex, so too has the complexity of lifesaving casualty care, sophisticated medical technology, specialized training, and advanced medical logistics, enabled by those dedicated medical professionals who deploy with and support the warfighter.

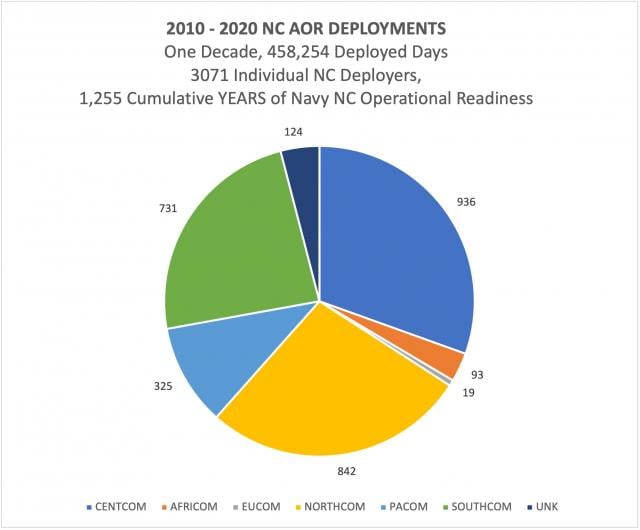

Wherever Sailors and Marines go, Navy nurses are and should continue to be present, but unless you have deployed to a remote, isolated forward operating base (FOB) in a combatant commander’s (COCOM) area of operations (AOR), you likely have never witnessed the independent, operational skills of Navy nurses in action. Over the last ten years, the demand signal for unique skills that Navy nurses bring to the fight has been strong and consistent. From 2010-2020, more than 3,000 Navy nurses deployed in support of every COCOM’s AOR, totaling 1,225 years of operational impact. (See Figure 1).

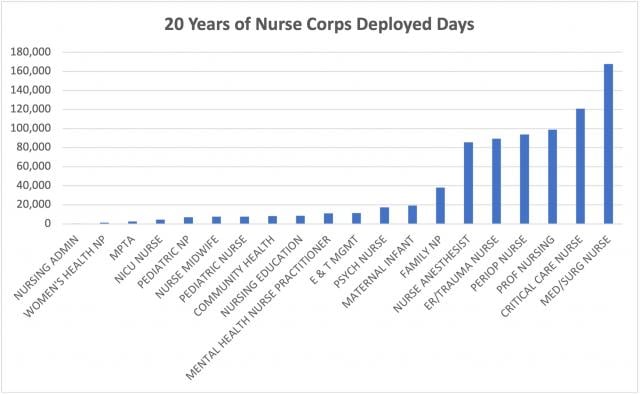

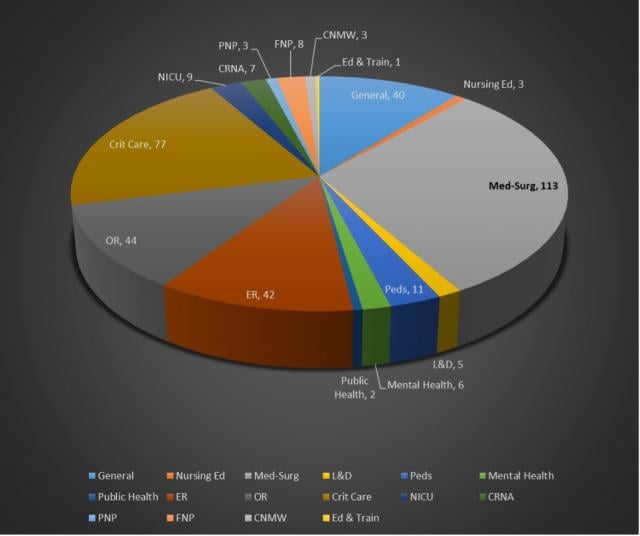

The continuous and surge operations of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom have called for high numbers and percentages of Navy nurses around the globe. The demand for Navy nursing’s operational response capability over the past two decades cannot be clearer (see Figure 2). Currently, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Navy nurses from sixteen discrete specialties have met the nation’s call and deployed to answer the Defense in Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) national emergency and will continue doing so in 2022 (see Figure 3). The critical role played by Navy nursing is illustrated by the significant increase in deployments during the Covid-19 pandemic and reflects the composition of the new Medical Response Team (MRT) platform developed specifically for DSCA response. These twenty three person teams deploy with a leadership and administrative support team of two Medical Service Corps Officers, four Medical Corps officers with hospitalist and critical care expertise, fourteen specialized inpatient Nurse Corps officers, along with a senior enlisted hospital corpsman and two enlisted respiratory technicians. One dividend of the DSCA response is that the lessons learned from these teams are informing the refinement of deployable modular medical teams to care for disease, non-battle injuries in the future fight. As they are for the MRT, Navy nurses will be an integral component of this new capability (see Figures 4 and 5). As it has since its founding, Navy nursing has met the mission and continues to respond to the many calls of the nation.

The lens of history provides some insightful parallels to issues facing the current Navy, and its relationship with its own Navy Nurse Corps. The Navy’s first nurses had to fight to serve, were largely “unseen” or dismissed (based on gender), by an officer class (of which they were not originally part). Yet, less than a decade from the Nurse Corps’ inception, nurses proved themselves an integral part of the Navy, directly supporting World War I military operations and working the frontlines of the influenza pandemic of 1918–19. Navy nursing history, especially at this time, is worthy of review, introspection, and deep, deliberate discourse. The second Superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps understood and captured the timeless essence of Navy Nursing:

“Wherever the United States through the medium of the Navy is managing the affairs of a people, the Navy Nurse must establish herself” – Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee (1918)

When war broke out in 1917, the Nurse Corps grew from 160 to 1,386 nurses in a mere eight months. Navy nurses were assigned to the transport ships USS Mayflower and Dolphin, and then during the war on board SS George Washington, Leviathan, and Imperator. The Nurse Corps projected capability and capacity that would be crucial to the efforts of war. Preparing for the surge of naval forces, Higbee partnered with the Red Cross to prepare a nation for its returning war wounded. In addition, she set up training sites for nurses and hospital corpsmen, ensuring a ready medical force with both extended reach and medical competence. Nurses were positioned in the Pacific, Haiti, and the Virgin Islands, where they taught and trained local nurses, growing nursing capacity on distant shores, and providing for America’s growing global reach which became especially important in the next war.

As World War I subsided, the influenza pandemic of 1918 swept through Europe and the United States, roughly on the level of the current pandemic. As with today’s transition in focus from decades of war to COVID-19, Navy Nurses turned their attention to the global health emergency. In spite of valiant efforts, and patient-to-nurse ratios exceeding 1,000:1, the influenza virus claimed more than 50,000,000 lives around the globe.

After the war, Higbee was able to achieve a pay increase for Navy Nurses and a uniform and specific insignia for the Nurse Corps. The first woman and only living nurse to be awarded the Navy Cross, Superintendent Higbee was recognized for her distinguished service and conspicuous devotion to duty. But it would not be until 1944, three years after her death and three years into World War II, that Navy nurses were granted full rank and equal pay, and not until 1947 that Navy Nurses were recognized as an official staff corps. Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee’s pioneering achievements have been recognized by the Navy, by commissioning the first Navy warship named for a woman in her namesake, USS Lenah Higbee ( DD-806). Currently, the second ship christened USS Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee (DDG-123) is being built and will be commissioned in the future.

Superintendent Higbee and the Sacred Twenty set the foundational high standards, the aspirational tenets of nursing service through extraordinary personal sacrifice, the obligation to teach and train hospital corpsmen, the character traits of a true and right moral compass, the driving passion, and a calling to lead and succeed in harm’s way for the original Navy Nurse Corps of 1908. All these original features stubbornly persist today—at the ready, transcendent, ever-evolving, improving, excelling, fully invested, and embodied in today’s Navy Nurses, who are battle-proven, responsive to every call from the front, and willing to serve under continuous strain and arduous conditions.

Navy nursing continues to advance; however, there are real risks and escalating threats from near-peer adversaries on the horizon (not dissimilar to events leading to both World Wars), and in the slowly dissipating aftermath of a deadly and horrifying pandemic (like 1918), nurses face challenges with force generation due to both national nursing shortages and anticipated future military reductions, incongruent with historic and present contributions. Navy nurses are in some ways still waiting for standing, account, visibility, acknowledgment, and full integration, assigned with, and on behalf of, the expeditionary naval forces for whom they dedicate their professional careers and life’s work. Ongoing military medical end strength reviews should continue to take into account the critical and irrefutable support nurses have provided to expeditionary naval forces, the life-saving care given to Sailors, Marines, and their families, and the care provided to the nation as a whole.

Navy Nursing Today

Navy nurses have now commanded hospitals and operations, led convoy missions in war zones, served as sole medical assets in remote and isolated settings, saved lives around the globe, returned wounded back to the fight or to higher echelons of care, cultivated international partnerships, served as diplomatic intermediaries, worked with government and non-government agencies, projected the power of Navy Medicine into every theater, against all threats, prevented and treated injury, promoted health, bolstered human performance, protected and strengthened the quality and resilience of naval forces, and led with caring and compassion for the past 113 years. Modern Navy nurses are ready to be counted and want to do more. As part of One Navy Medicine, Navy nurses are prepared to support and offer viable solutions to expanding capacity for DMO and EABO, and closing gaps in the future fight.

The Navy Nurse Corps is well trained and educated (see Figure 6). In 2010, a specialized subset of 23 Navy nurses had earned their Ph.D. By 2020, the Navy Nurse Corps had 203 nurses who had earned the title “Doctor” (many now with the clinically focused doctor of nursing practice or DNP). Another 690 Navy nurses held master’s degrees. These are specialty prepared experts in critical care, medical surgical nursing, public health, emergency/trauma nursing, nursing informatics, and education & training, to name a few concentrations.

Many advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) in the Navy Nurse Corps also are designated licensed independent practitioners (LIPs). These nurses function independently and collaboratively, without clinical supervision or additional oversight. They assess, order tests, labs, x-rays, diagnose conditions, prescribe medications and treatments, and follow up with their patients. Examples of LIPs include family nurse practitioners (FNPs), certified nurse midwives (CNM), mental health nurse practitioners (MHNP), and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNA). Each of these specialists has 12–16 years of direct clinical practice upon graduation. Navy Medicine readily employs many non-LIPs in the fleet; these include physician assistants and independent duty corpsmen, many fresh out of training with limited clinical experience.

Nurse LIPs have proven their mettle in isolated, forward-deployed operations, at sea, with the Marines, and on isolated FOBs as the senior medical officer (and only medical officer asset) in combat zones, and as the sole clinical provider in remote strategically located sites, such as Romania, Poland, and Bahrain. Despite their qualifications, these nurses frequently have filled “substitution” roles for other personnel, including physicians, physician assistants, Independent Duty Corpsmen (IDCs), and even General Medical Officers (GMOs). As a result, the operational footprint of these nurses has been largely unquantified.

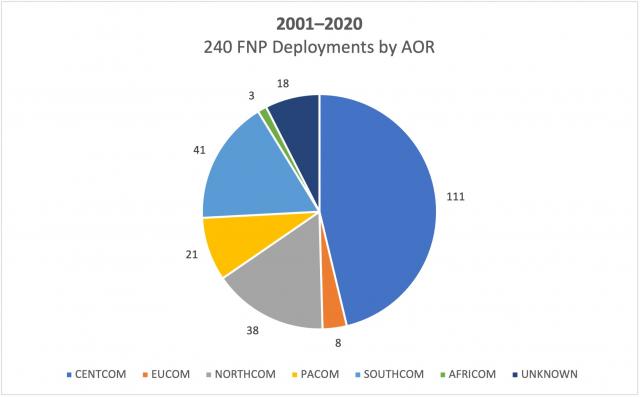

A specific example is illustrated by the family nurse practitioner— a specialty community facing a 40 percent reduction, because FNPs have been overlooked as a historic platform “requirement.” However, FNPs have been highly tapped for operational roles during surges in operations (see Figure 7). In the past two decades, the FNP community deployed days totaled 104 years. Without codified billets in the fleet or alongside Marine forces, the FNP community is easily dismissed as a shore-based, military treatment center–centric entity.

A recent proposal to pilot FNPs in the destroyer (DDG) community was met with some interest, in acknowledgment that evolving DMO and EABO strategy will produce new challenges to warfighters and to Navy Medicine. Kinetic clashes of navies and air forces may occur without warning and result in immediate high casualty rates and loss, a situation not faced by American forces since World War II. Any survivability given the threat will be enhanced by improvements to FHP and REVIVE vector concepts:

- Pre-injury condition (individual and population mental and physical fitness, human performance variables, safety, injury prevention, wellness of mind, body, spirit)

- Immediate, advanced life-saving intervention (classic combat casualty care, Advanced Trauma Life Support and Trauma Nursing Care)

- Prolonged “field” care—this is nursing (direct bedside care, infection prevention, advanced wound care, fluid management, and pain management skills). Corpsmen are taught these skills by nurses

- Expedient evacuation (including en route care) when able, given DMO challenges

- Credible cradle-grave, age-based competency; plus, women’s health/Female Force Readiness (20 percent of force and growing)

FNPs (APRN LIPs) bring unique core skills and improved outcomes to each of these areas, including combat casualty care. At baseline, all professional nurses deliver patient-centered, holistic care, grounded in health promotion, wellness, behavioral health, injury/illness/chronic disease prevention and population health. This diversity of skill and ability to train medical staff colleagues, corpsmen, and warriors (self-care, buddy aid) is an immediate force multiplier.

Navy Nurses have been decorated and honored as heroes for their actions in armed conflict, earning the Navy Cross, Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, and Combat Action Ribbons. Navy warships are named in their honor. They are represented by memorials and in museums on the National Mall. They have been immortalized in films and television programs. And over the past 113 years, they have also evolved—rapidly—and may be wholly unrecognizable, for those who have not recently served alongside, or are in any way limited in their understanding of what and who your current Navy nurse is. The Navy should start incorporating navy nurse leadership skills and specialty contributions into war-games and TTXs, building medical capacity for DMO/EABO through requirements-based, and appropriate billet alignment to and within the expeditionary naval forces, as well as all soft power applications. Navy nurses will bring their best and always improve U.S. odds at winning—wherever and whatever the battlespace demands.

1. Esther V. Hasson, “The Navy Nurse Corps,” The American Journal of Nursing 9, no.6 (March 1909), 409–15.

2. An Address by Mrs. Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, 25th Anniversary of the Navy Nurse Corps (given in Winter Park, FL).